Ask a Caltech Expert: JPL Scientists on Water Resources and Drought

As part of Conversations on Sustainability, a webinar series hosted by the Caltech Science Exchange, JT Reager, Earth scientist at JPL, which Caltech manages for NASA, and Indrani Graczyk, program manager of the NASA Western Water Applications Office (WWAO), located at JPL, discussed their research into water resource management and how JPL and NASA satellites help individuals and government entities make difficult decisions in the face of climate change.

Graczyk and Reager explain how satellites have made possible a golden age of water monitoring, how modern droughts compare to those from centuries ago, and how a complex maze of rules and rights governs the H2O that comes out of your tap.

Here, they talk with Caltech science writer Whitney Clavin.

The questions and answers below have been edited for clarity and length.

Can you give us an update on the status of the drought in California?

Graczyk: The reality is, we've had two dry years in a row, and that has led to these conditions that parch soils, with not a lot of snow up in the mountains to melt and run into our streams. The other thing that people hear a lot is that reservoir levels are at some scary lows right now. Lake Mead got to the point where it was so low that the states that had historically been able to take water from the Colorado River had to reduce their allocations.

I think people who lived here 20 or 30 years ago would remember that the months between November and February were wet in general. Now those months are dry, except for three or four storms, and the difference between having three storms versus five is a difference between being in severe drought versus being completely out of drought. We're getting our water from a lot of these extreme events, and it's hard to predict whether we are going to get enough water to get out of drought or not.

How do the last two years compare to historic droughts, and how has global warming affected this?

Reager: There's a wonderful researcher named Park Williams of UCLA who has done a series of papers showing that the past 20 years, starting in 2001, are probably the driest 20 years that we've had since the year 1200. They're calling this last 20-year period a mega-drought.

In California, snow is very important. We have snow that hits the Sierra Nevada in our rainy season, the winter, and then the gradual melt of that snow through the summer. That snowmelt, which runs into the Central Valley for agriculture and for residential use, usually melts through the summer, through into the fall. What we're seeing with climate change is we have less precipitation falling as snow, and then it's melting earlier. It's shifting the snow season. Snow is like our battery—it is how we store water through the summer. And with climate change, we're really seeing the size of that battery capacity diminishing.

How do we make sure farmers get enough water and that we get drinking water?

Graczyk: California developed a system here called "first in time, first in right," such that if you started using the water, then eventually it became enshrined that you had a right to that water. So, our system has senior water rights and junior water rights depending on when you made your claim for your water. In times when we have a lot of water, everybody gets the water that they have a right to. In times when there's less water, the folks that have the oldest water rights are the ones that will get the water and the people who have younger water rights will get less. This whole system is administered by the California State Water Resources Control Board. And then there's also the California Department of Water Resources that tries to ensure that our water resources and our water infrastructure are maintained and are of sufficient quality.

In other words, there is a very complex structure to determine who gets how much water and how it gets to them, and the water quality standards. As somebody who came into this five years ago, I'm still amazed that it all works so well. People are working together across all these layers to get water to everybody who needs it.

How are satellites helping in the process of water management?

Reager: We are in a golden age of water information for this planet, where we have more information streaming in now from satellites than we've probably ever had at any point in human history. The challenge is just making sense of that data. We have algorithms to convert it into a form that we all recognize, like snow depth or soil moisture. The next step is to take that information and wrap it into a contextual understanding of what's happening on the ground. That's when it really brings understanding. Bridging that gap between data information and understanding is the task of the scientist.

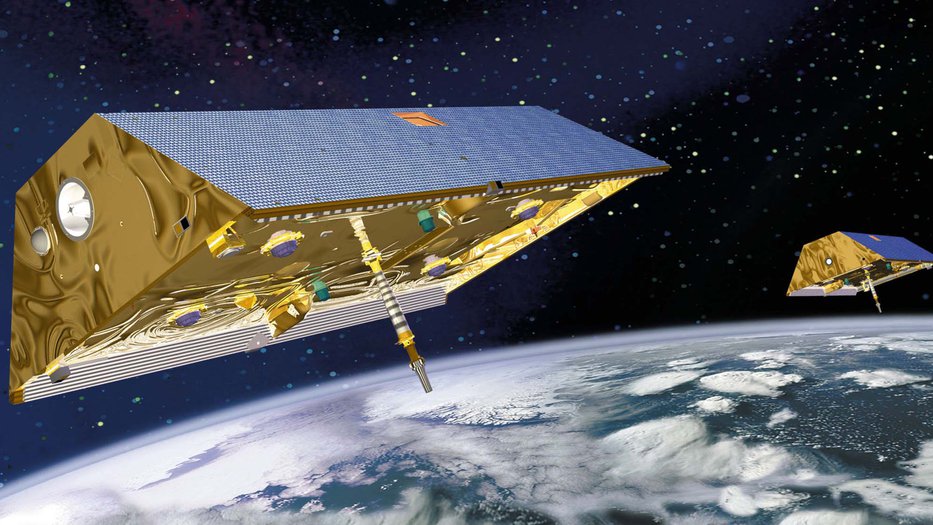

By far my favorite mission that JPL has ever launched is called GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment). It consists of two satellites that orbit the Earth in tandem, one following the other. As they pass different portions of the planet, they measure differences in the gravity field of the planet. The only thing that's heavy enough and moves fast enough to cause major changes in the Earth's gravity field is water.

How does the WWAO use that data to help people on the ground?

Graczyk: Even before the Western Water Applications Office came into being, there were scientists like JT who took the information and insights from looking at satellite data and reached out to water managers with useful information. For example, NASA and the California Department of Water Resources developed a partnership to make a forecast about how much water would melt into the reservoirs based on measuring the snow in the mountains or measuring the effects of removing groundwater.

The WWAO is trying to build on that. We're trying to be more deliberate. We reach out to water managers and talk to them about their needs and their challenges. We try to bring people together with similar needs and challenges and identify what this data would need to look like, what product they need in order to help them with their decisions. And then we come back to the scientists and work together to put it into a form that is useful for water management. So, it really is trying to take all the good science that's been done and make it useful for water management.

One example: We had a scientist here at JPL, that worked with Department of Water Resources to develop a system called the Airborne Snow Observatory. It's a plane that would fly over the Sierras. By taking a lidar measurement—which is kind of like bouncing light off the ground and measuring how much time it takes to come back—you get a really accurate measurement of the height of the ground. Then, if you come back when there's snow and make that same measurement, that difference is the snowpack. This was extraordinarily useful information.

Here are some of the other questions addressed in the video linked above:

- How do you measure drought and wet or dry years from centuries ago?

- What challenges do you face in translating the space-based scientific data to policy makers and nonscientists?

- Shouldn't global warming mean there is more water in the air because of evaporation? Why is California getting drier with climate change?

- What future JPL missions are you most looking forward to?